For the month of January, I will be participating in a blogging challenge where I will receive topics to write about for each week in January. Below is my first submission!

This post is part of Blogging Abroad’s 2017 New Years Blog Challenge, week one: Global Citizenship.

Many of my fellow Peace Corps Volunteers and I live in the boonies. We traverse uneven roads while perched on uncomfortable bike taxis, we endure long minibus journeys, and we walk up and over mountains to access our sites. To reach the closest Peace Corps Volunteer, I must travel over two hours. Yet, despite this isolation, each day I am reminded of my community’s connection to the “outside world.” Contrary to the assumptions I had before coming to Malawi, my village is not an isolated entity where news of what’s happening in the capital takes weeks to arrive. My notions about Malawi’s disconnect from the rest of society, along with many other fallacies, have been shattered. Every day I notice countless ways in which my village interacts with the global community, whether it be through cultural, economical, or political exchanges. Here are 5 ways in which I’ve observed globalization in my own village:

1). Azungu BO! My first example comes from the vast amount of borrowed language that I hear spoken in Malawi. While there are over ten local dialects, each area utilizes “Chichewa-lized” terms, or words borrowed from other languages that are then made to sound like Chichewa (the national language). For example, foroko means fork, felempani means frying pan, sikulu means school, buku mean book, and poto means -you guessed it- pot. Some of them are so similar to English that it cracks me up! My favorite cognate, however, is bo, a colloquial way of saying hey. Anytime I walk around my village, I am inundated with bo’s or bo-bo’s. I’ve asked many people what the word means, but most have responded with kaya, who knows! I finally learned that it was adopted from French, either from bonjour or bon, meaning hello or good, respectively. Over time, bo morphed into an informal greeting and spread across the entire country of Malawi. Therefore, every day when chatting with my neighbors about how sikulu was that day, or saying bo to my friends, I’m reminded of how interconnected the world is based solely on common languages.

Bo-bo!

2). Luxury lakeside lodges. Within a few months of getting to my first site, I decided to bike from my village to Lake Malawi. I followed a tiny dirt path for about 15km, passing mud-brick houses with thatch roofs, children playing with makeshift toys in tattered clothing, and farmers hoeing away in their fields. The usual. When the path ended, I arrived at the beach and walked down the shore, wondering what I would find in the small fishing village. To my surprise stood a gated, three-story lodge with a manicured lawn, a pool, and a fancy Indian restaurant! I was beyond disbelief. Later I learned that a bit farther down the shore, on a little island, there sits a lodge that costs $300 per night per person! There I was, biking from my village in which the average person lives off of about $7-10 each month* to a lodge where tourists were spending over 40 times that amount in a single night. As more and more tourists visit Malawi -“tagging” their locations on Instagram, posting reviews on travel websites, or uploading photos on Facebook- the more exposure isolated places like these obtain. While exchange of cultures between tourists and locals can be wonderful for both sides, tourism can completely alter the lives and culture of local people.

Mayoka Lodge, Malawi

3). All of the stereotypes. Being Caucasian in Malawi not only warrants a lot of attention, but also generates countless assumptions. Almost everyone believes that I have copious amounts of money. They are astounded when I tell them that there are poor people in America. Many wonder why I don’t dress my dog in human clothing**. Others believe that the US has no trees and is just a big cement-filled city. Lastly, everyone thinks that all of my fellow American citizens have light skin. These stereotypes about Americans are most definitely perpetuated by globalization. Picture my neighbor, Malizani, going to the market and watching a film played on a shopkeeper’s TV. Most of what he sees is cheap action movies starring heterosexual, white Americans who live in big houses in the city. These quick glances into the lives of foreigners were not possible in rural villages even 20 years ago. Yet, with the help of foreign aid, Malawi has been developing its technology and infrastructure, allowing Malizani to form stereotypes about Americans. The spread of technology has perpetuated the spread of foreign cultures, values, and lifestyles into any space with a functioning television -whether they are true depictions or just something Hollywood has dreamed up. While many Malawians seem to rely on these stereotypes for their understanding of Americans (initially created by globalization), I believe that as we delve further into becoming one integrated, united world, we will all have a better understanding of each other.

4). Maize rules everything around me. How so? During the planting season, chiefs promulgate a change in livestock laws to protect sprouting maize. During growing season, teachers may not show up to school because they are busy weeding. During harvest season, it’s difficult to plan community projects because no one is around. After harvest season, there is a spike in weddings and initiation ceremonies when families know that their friends have cash to give. I think I could go on and on explaining how life revolves around maize in Malawi. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, maize accounts for 50% of the average daily calorie intake of Malawians. Imagine half of your plate at every meal being filled with maize! Five hundred years ago, this was certainly not the case. Malawians traditionally cultivated millet and sorghum, both drought-resistant crops. However, as the continent of Africa was “discovered” and colonized, foreigners brought with them preconceived notions on what would be best for African farmers, along with new plants. Specifically, the Portuguese brought maize to Malawi around 1500 AD. This fatal introduction has since led Malawi to depend almost exclusively on an extremely vulnerable crop for their staple food. (You only need to look at this year’s food crisis to understand the enormous impact that erratic rains have on maize, and therefore life, in Malawi). If Europeans hadn’t sought to expand their empire and forcefully insert their flawed-for-Africa farming knowledge, where would Malawi be? If Malawi hadn’t entered the global arena, would my neighbors still be farming millet and sorghum and therefore surviving the climate-change induced droughts that have been occurring?

5). I’ll flash you. One of the easiest, most obvious signs of globalization in my village is the widespread use of cell phones. When my mom was visiting in June, she wanted to take a picture of a woman carrying a hefty load on her head. However, when she noticed that the woman had a cellphone strung around her neck, my mom innocently commented that she wished it wasn’t there. The cellphone somehow marred the scene. While very unexpected for visitors, this clash of technology and tradition is now a part of Malawi. Technology has apparently jump-frogged development, bringing cellphones to people that can barely afford to feed their families. How does this related to flashing? In Malawi, to “flash” someone means to call their cellphone for a few seconds and then hang up so that they are aware that you are trying to reach them. This is done so the person calling does not have to use their precious and costly minutes. While most of my fellow community members have phones, few have the capital to make even a one minute long phone call every other day. The spread of new technology to remote areas can be startling and awkward, but has also brought great development to Malawi such as mobile banking and an increased ease of communication.

Hopefully you now have a better understanding of how Malawi can be affected by the rest of the world. As international travel increases, as technology spreads, and as language is adapted, the world shrinks. This interplay between cultures, peoples, and economies requires us to be global citizens. We must examine our choices. For example, is the lodge that I’m staying at exploiting a local culture or is it working with local groups to develop sustainable businesses? Is donating my old clothing “to Africa” really helping the people of Malawi, or is it impeding their textile industry? Are the crops that we are urging farmers to plant actually helping? Is donating tons of maize to Malawi each year just sustaining Malawi’s dependency on maize? Being a global citizen means educating yourself so that you can answer these difficult questions. It means extricating yourself from false stereotypes and not relying on media portrayals for your understanding of the countless different African cultures that exist. It means being aware of local cultures and how you present yourself when traveling. While I haven’t yet processed all that I have learned through Peace Corps, I do know that this experience has greatly encouraged me to be a true global citizen.

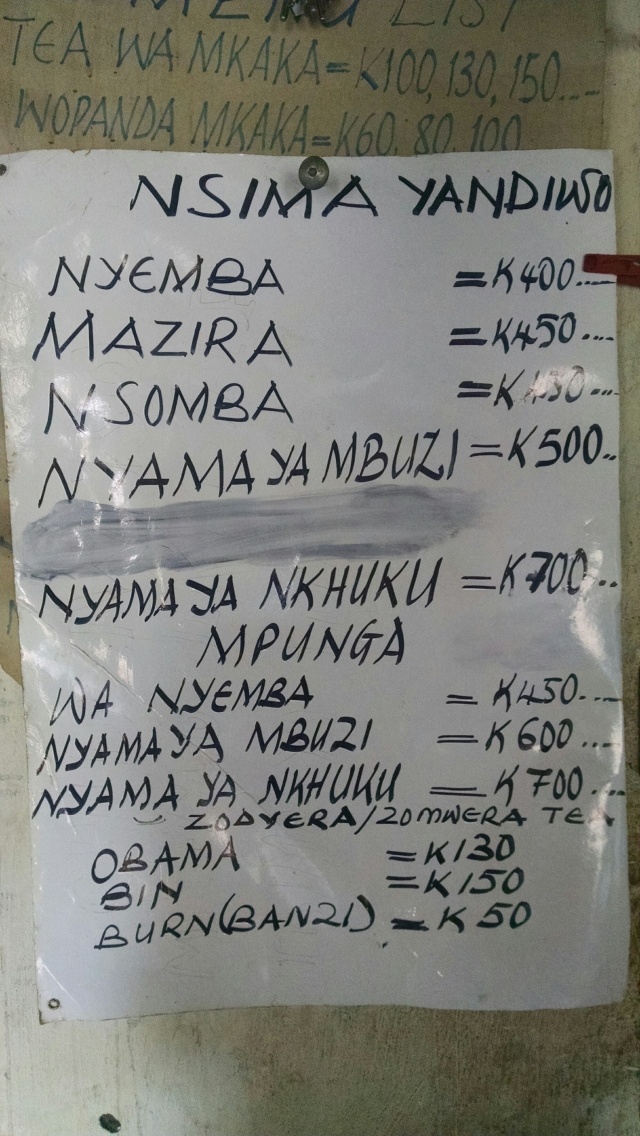

Bonus picture! This is a snap I took today in my favorite restaurant. Check out the third to last item on the menu, OBAMA. Yes, a popular bread here is named after The Obamas. I approve!

*According to a small survey I did in my catchment area

**Okay fine, I used to dress up my dog…

Congratulations on your first Blogging Abroad post. I am looking forward to the other January posts.

Question….why aren’t the Malawians planting millet and sorghum anymore? Globalization can include crop diversification, not just technology.Are there any NGO’s dealing with this issue?

Just wondering….

Your blogs always educate, enlighten and pose questions. Keep up the excellant work.

Miss you much,

Aunt LB

LikeLike

Hi Laurie! I really don’t know how they transitioned so quickly- I would love to find a book about Malawian agriculture when I get back home. I was talking to my neighbor the other day about it and she thinks that millet & sorghum cultivation is on the rise again. A lot of NGOs have begun teaching about crop diversification, including my fellow PCVs and Feed The Future. Other initiatives encourage high-nutrient crops, like orange fleshed sweet potatoes that help combat low Vitamin A levels.

LikeLike