Hi folks! I’ve been finished with my Peace Corps service for over two years now (and still haven’t gotten around to writing about adjusting back to living in the States…maybe one day!) In the meantime, I’ve opened up an old photo blog that I’ll be using from now onwards for my travels, which can be found here. I’ll leave this Peace Corps Blog open for those looking for information on serving in Malawi. Cheers!

My Personal Nsima Journey

And now, what you’ve all been waiting for… A comprehensive guide to making nsima!

As you may know if you are an avid reader of my blog, nsima is Malawi’s staple food. It is consumed twice a day, every day, and if you haven’t eaten nsima (even if you’ve enjoyed a lovely meal with other types of food), then you haven’t eaten– period. Chances are that if you ask a Malawian about their favorite food, it will be nsima.

So what does this ever popular food taste like? The best description I have heard comes from my friend Corey who described it as unflavored, congealed grits. It’s bland, boring, and starchy. For this reason, nsima is always consumed with ndiwo, a side dish such as fish, greens, meat, beans, eggs, etc. The real purpose of nsima is to keep your belly full and act as an edible utensil for delivering other food to your mouth.

So how is it made? To answer this question, I decided to embark on a mission to follow one patty of nsima from it’s conception to consumption.

Step 1. Prep & plant.

Prior to planting, you must prepare your plot of land. For Malawians, this means burning old brush and forming rows. As I don’t have my own plot of farmland, I decided to just plant ten seeds in my backyard and see what happened. This, of course, has inspired laughter all over Kasinje, along with countless jokes about whether my measly harvest is going to be enough to feed me for the year. Telling people that I only planted ten stalks is my go-to joke now, as it always gets a hearty laugh.

2. Wait & weed.

The next step is to wait for about three months for the maize to mature. Hopefully, it won’t rain too much or too little and your harvest will be bountiful. (Due to the effects of global warming, Malawi has not only seen an increase in droughts & flooding, but high variability in the start time of rainy season, making it increasingly difficult for farmers to time their planting correctly). If the seedlings are destroyed from planting too early then families are forced to re-plant, granted that they have extra seeds. During this growing period, my neighbors are always extremely busy weeding their fields.

Step 3. Harvest!

This was the most exciting part for me, as I had been bragging to all of my friends and neighbors about my maize for months. Last week, it was finally ready! Once the maize matures, the stalks begin to dry and turn yellow. This is when Malawians begin chopping down the stalks and gathering them into huge piles. This way, when it comes time to remove the ears from the stalks, it’s a bit easier. Last week, I helped a friend with the slashing and stacking and it was certainly a chore. (I’m mostly surprised I didn’t trip over one of the rows in the process of carrying an obstructive load of stalks on my shoulder).

Step 4. Shuck corn and remove the kernels.

After assembling the stalks into piles for convenience, the ears are removed and husks are shucked. The husks are then typically loaded onto an ox cart and delivered to the family’s home, where most of the corn is stored in an extra bedroom. It’s amazing seeing an entire room filled to the brim with corn! While my harvest was less impressive, I was still extremely proud, as I felt I had become a true Malawian. Harriet, Sipe, and I shucked the corn in my backyard and proceeded to the next step.

Step 5. Sun dry the kernels.

After removing the kernels from the cob, they are spread out on maize sacks and put in the sun to dry. This is definitely a team activity, as the corn must be fiercely guarded from goats, cows, and chickens. Once fully dried, the kernels will make a certain noise when you swish them around on the mat and it is only then that you know it’s ready.

Step 6. Mill the maize.

Even though the maize mill is one of the most iconic spots in the village, I embarrassingly had never been until last week. I walked with my little bucket of maize on my head while women carrying huge basins passed by. When we arrived, Harriet and Sipe showed me the ropes and I learned that milling maize is as easy as pouring the kernels into a funnel and placing a bucket underneath to catch the corn flour.

Step 6. Cook nsima!

As aforementioned, nsima is prepared twice daily, which means that by the age of 10, all Malawian girls are experts. This also means that when I occasionally cook nsima for myself, it is always critiqued. To begin, a pot of water is put on the fire and heated up until steam arises. After that, a few scoops of corn flour are added and stirred in. You then must wait for the porridge-like mixture to thicken and boil for awhile. Once the color slightly changes and the mixture is of the correct consistency, a bit more corn flour is added and the aggressive stirring process begins. Nsima must be stirred constantly for the last five minutes that it’s over the fire, and there is a very particular way in which Malawian women do so. (Did I mention that they grab the pot with their bare hands while stirring? Check out Harriet below).

Step 7. Serve the nsima.

Finally, the nsima is scooped out of the pot with a special spoon called a chipande and plated. It can either be enjoyed communally in a big stack to be shared by the whole family, or placed on separate plates with the ndiwo.

4 Things That Malawians Are Doing Better Than Americans

1. Eating seasonally & locally available foods. Without electricity to power refrigerators, major grocery stores to stock overly processed foods, or supply chains to distribute out-of-season fruits, community members mostly rely on local produce. If you need vegetables, you walk a mere two minutes to the big mango tree where a line of amayis will be waiting with their day’s pick. If you want fresh maize, you simply pluck off an ear from the stalks that surround your compound. Malawians don’t amass much trash because instead of buying tiny snack packs that contain six chemical-infused apple slices, they eat whole foods that come directly from the land. Furthermore, most Malawians only eat foods that are in season. Waiting patiently for mangoes to ripen is difficult, but it makes them even more delicious!

2. Pile diving. This refers to the act of rifling through huge heaps of used clothing on market days. Usually, (at least in my village), crazy salesmen stand behind the mounds shouting out prices, dancing around, and mixing up the piles so that customers can see all there is to offer. The selection is completely random, from long red velvet overalls, to Ralph Lauren jackets, to Cape Cod t-shirts. You never know what kind of gems may be lurking in those piles, but they will probably cost less than a dollar. This kind of shopping beats any mall excursion any day. Plus, it’s all outside in the fresh air!

3. Raising self-sufficient children. In the US, parents go to ridiculous lengths to make sure that their children are safe. They douse their kids in Purell, put them on leashes, and restrict them to playing in limited spaces. In Malawi, children run around with knives and begin farming at the age of five. While I admit the knives may be a little dangerous, the point is that Malawian children have the freedom to make their own mistakes and learn from these experiences. This allows them to be capable of babysitting their younger siblings at age eight, managing donut sales at age ten, and cooking over a fire at age twelve. Malawian kids are resilient, resourceful, and a bit wild. (Just like Peace Corps Volunteers).

4. Nurturing a sense of community. Back home, I barely knew my next door neighbors. In Malawi, that would be unimaginable. Neighbors are usually literally family, but also figuratively family, in that they take care of each other as if they were true brothers and sisters. When a family sits down to eat, they invite anyone that is around to join, regardless if they’ve prepared enough food. When someone passes away, the entire village drops what they are doing to attend the day-long ceremony. This sense of community extends even beyond the village, where the best example I can provide is the camaraderie that develops among the hodgepodge of passengers on a typical minibus. After only twenty minutes together, the passengers will be sharing snacks, cracking jokes and making tsk-tsks and ay-ay’s (typical Malawian noises) in perfect unison. I love it. Now, imagining going back to America where people sit in morbid silence, tapping away on their smartphones, I can only cringe.

5. Road snacks. The best part of road snacks is feeling like a TOTAL BALLER. All of Malawi’s major roads are lined with vendors who sell mandasi, corn on the cob, hard boiled eggs, sodas, apples, peaces, lollipops -you name it. When your minibus pulls over (approximately every 8 minutes), the bus is swarmed by people selling their goods through the bus’s windows. It. Is. Awesome. You can dine on an array of delicious treats without even leaving your seat! (Yes, America has drive-thrus but road snacks require 1/10th of the effort at 1/10th the price.)

Highlighting Hospitality

Did you know that Peace Corps celebrated its 56th birthday this week?! In commemoration, volunteers all over the world have been sharing stories relating to a central theme: highlighting hospitality.

While I’m sure that volunteers in other countries can identify with this theme, I have a hunch that it was specifically chosen for Malawi. The culture here exudes hospitality, evidenced by the assumption that visitors are welcome to stay whenever and for however long they wish, or by the soothing phrase, feel so free, which encourages guests to feel at home. For me, the most patent display of hospitality is seen within the food culture. Right now, as rainy season comes to an end and gardens are overflowing with greenery, it is impossible for me to go anywhere without receiving an armful of fresh maize, a just-picked pumpkin, a plate of okra, a bag of cow peas, or whatever else is available. The custom of imparting food upon your visitor is astonishing. Many families are just muddling through this year’s hunger season, yet they will eagerly give the white bwana whatever they can. If I just stop to chat with my neighbors for even a few minutes, I will walk away with roasted corn. If there are no more cobs on the fire to give, my neighbor will break off the piece she’s eating to share with me.

Although I have come to love the local foods, my favorite display of Malawian hospitality involves something slightly sweeter and more American. It occurred during my first few weeks at site, a time when I didn’t have strong language skills, friends, fire starting abilities, or even furniture to sit on. I loved the adventure, but I was lonely not having anyone in my community to connect with on a deeper level. One night, shortly after the sun set, I heard a voice outside. “Odi! Odi!” the voice called. I was apprehensive to open the door as I didn’t know who would be standing on my stoop in the dark. (If you didn’t know, PCV’s turn into pumpkins after 6:30pm and thereby never leave their houses at night). Anyway, I opened the door to find my supervisor holding out a tupperware of -believe it or not- ice cream!! I almost started crying, not only at the site of the creamy deliciousness in front of me, but at his immense thoughtfulness. John had purchased the ice cream in town and biked it nine miles to my house. He said he thought I must’ve been missing American food, but hoped that I was enjoying my time in Malawi. Thinking back on this, I am floored that he would buy such a frivolous, expensive item for me just to make me feel welcomed. Yet, this type of gratuitous hospitality, in which Malawians go above and beyond to make their guests feel welcome, is nothing special. I could tell you dozens of stories that exemplify just how welcoming my community members have been. I do live in The Warm Heart of Africa, after all.

Some of my favorite iwes cooking me pumpkin leaves on my front porch

The Musings of a Soon to be RPCV

The past month has been a whirlwind of emotions, people, places, and experiences. In mid-January, I had the pleasure of hosting four PCVs at my site and implementing a project that I had begun conceptualizing in October. Over the course of three days, my fellow PCVs and I visited three primary schools and taught malaria lessons to 757 children. The lessons were delivered via stations, in which each PCV was paired with a teacher that had been trained on their topic. I designed the lessons to be interactive and fun, incorporating songs, hands-on demonstrations, and cheers. Surprisingly, our time with the kids went really well! I was excepting at least a few teachers to be absent or for the rain to completely ruin the project, but we managed to implement the stations with relative ease. (After working in Malawi for two years, you expect at least one major pitfall). The students also showed, on average, a 37% increase in malaria knowledge, which made me happy!

After visiting the three schools, our culmination event was a grand malaria rally at the secondary school. I had been working with my Malaria Club the past few months to develop songs, dramas, poems, news reports, and raps about malaria. We also invited two of the most popular football teams and two netball teams to compete for new balls. Lastly, after training a local Youth Group on malaria, the members were invited to perform a drama on how malaria can affect farmers and businessmen. The day before the big event, it began raining at 2pm, continued throughout the night, and showed no signs of stopping right up until the event. By some miracle, the skies cleared up, the water dissipated, the DJ arrived only one hour late, and a huge crowd of about 400 community members gathered. The students did an amazing job performing -despite a rowdy crowd of children- and I was one proud PCV.

The morning after our rally, the other volunteers and I departed my house at 7am. Time (for me) to go to Cape Town to meet my best friend! This was the first international vacation I had taken since arriving in Malawi (besides a two day stint in Zambia), and I certainly got a taste of culture shock. When I arrived, I could not comprehend how clean and convenient everything was! I loved the diversity, the warm people we met, the natural beauty that surrounds the city, and of course, the sushi. I would not be surprised if I called it home in a few years. Another thing I thoroughly enjoyed in Cape Town was meeting other Malawians! Although it was a mere 10 days out of the country, it was so comforting to overhear Chichewa being spoken and to strike up a conversation my fellow countrymen. (Shocking the Chichewa-speakers with my skills was highly entertaining too!)

After leaving Cape Town, I headed back to Malawi and joined my cohort for our last ever conference. This was a time for us to be medically examined, say our goodbyes, review resumes, prepare ourselves for culture shock, and learn how to put our experience into words. I realized through this conference just how much I admire my fellow PCVs. Our group is the most talented, resilient, clever, weird, supportive, diverse, hilarious, intelligent group that I have ever been a part of. I know that everyone in my group has gone through some dark, difficult times, and am proud to say we have all struggled and overcome these difficulties together. Even though there are many people in my cohort who I wouldn’t say I’m close with, I feel like I could go to anyone for support, knowing that we will share a lifetime connection. (If you couldn’t tell, the end of the conference became quite emotional for a number of us who were just starting to realize that never again in our lives will we be a part of something so special).

Now, I am back in my village and have been busy reflecting on these sentiments. Returning after being away for such a lengthy time has made me realize how much I truly enjoy the people and way of life in Malawi. As I rode in on my bike taxi last week, my neighbors shouted out “Welcome back!” and the kids announced, “Chiri is here! She has arrived! She’s around!” My neighbors laughed as I came in, telling me how much they missed me and how worried they were about me. My landlord’s family lightened up when they saw me, and his daughter eagerly alerted me to the state of my exploding garden. Although I was a bit apprehensive to transition back into village life after my luxurious time away, I was delighted to be reunited with my community. That night, when I crawled into my dingy bedroom with a belly full of nsima, listening to the chatter of the village outside, I felt at home more than ever.

Now, knowing that I have less than two months left, each day in Malawi has become more meaningful. When I’m sharing tea with a stranger on a straw mat in a dimly lit room, I ask myself, when will I ever be able to do this again? When my youth group members and I laugh together during a condom demonstration, I think, where will these kids, who I have come to adore, be in ten years? When I take the long way to work, ambling down paths surrounded by maize, I ask, what other time in my life will I be so comfortable in a foreign land? Lastly, when I chat with Harriet on the stoop of my porch I muse, will I ever see these people again -the ones who have supported and loved me over the past two years?

While these questions are difficult to ignore, I’ve been trying my best to enjoy the little moments that I will never get back. I’m taking in the beautiful and vast night skies, I’m chatting lazily with the agogo next door, and I’m feasting on the local fare, for I know that life will never again be the same.

Harriet and me showing off my maize!

Straying From the Single Story: An Interview with Mrs. Mangochi

”She had felt sorry for me even before she saw me. Her default position toward me, as an African, was a kind of patronizing, well-meaning pity… There was no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of a connection as human equals.”

This is a quote from a TED Talk by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie called “The Danger of A Single Story.” In this talk, Adichie discusses how we have the tendency to develop very myopic ideas about other cultures based on the news we watch, literature we read, and the stories we tell. For example, the single story that many people tell about Africa is that it is “…a place of beautiful landscapes, beautiful animals, and incomprehensible people, fighting senseless wars, dying of poverty and AIDS, unable to speak for themselves and waiting to be saved by a kind, white foreigner,” says Adichie.

In order to do my part in chipping away at Malawi’s single story and interjecting some complexities, here is an interview with Rosemary Mangochi. Mangochi is a Biology and Mathematics teacher at Khola Secondary School. She has a Bachelor’s of Science in Education and has been teaching for 23 years. I had the fortune of meeting her last year when I was looking for a teacher to help with Malaria Club and since then, she has become one of my closest friends in Kasinje.

Mrs. Mangochi (bottom left) and I pose with our Malaria Club members

Mrs. Mangochi, what was your childhood like?

“I grew up in Nsipe, Ntcheu with my parents and seven siblings. My father worked as the general manager of a wood company. My mother was a teacher at the local primary school. We were somewhat wealthier than the other families and lived on the outskirts of a larger town. When I reached Standard 5 [5th Grade], I was sent to a Catholic Boarding school five hours away. My mother said the best way to raise a girl is to take her from the home environment and confine her in a Catholic School.” Mangochi explains that after primary school, she went on to a private secondary boarding school in the capital of Lilongwe and then did her Bachelor’s degree in Mzuzu.

How did you decide to be a teacher?

“I think I took after my mother,” Mangochi reflects. “When I was in secondary school and the teacher was absent, I would get up in front of the class and start teaching my friends,” she comments, chuckling. “I remember admiring my agriculture teacher because she was always dressed so nicely, looking very smart. So I wanted to teach agriculture.”

Who inspired you to reach your goal of becoming a teacher?

“I used to live in Blantyre for part of my childhood. We lived on a street where high-ranking officials worked. So my siblings and I would watch them every morning going to work, and we admired that. At my secondary school, I also had a lot of female teachers who were very encouraging.” She pauses for a second and then adds with a smile, “And they were coming to school in cars.”

What kind of obstacles have you faced during your career or lifetime?

Mangochi starts by explaining a debilitating practice that is all too common for girls in Malawi. “When I was in Standard 2, [2nd grade] my mother told me to leave school so that I could take care of my brother. That means I had to repeat that year.” She continues reflecting on her childhood, “And when I started menstruating, there were no cotton wool, pads, or whatever. So we had to use rope tied around our hips with a piece of cloth tied to it between our legs. It would cut our sides and be so painful. We could not go to school during that time. We were forced to bathe in the river. That was too hard.” Mangochi goes on to explain the hardships that most Malawian women face here, not excluding herself. “Almost every chore is done by a girl or woman here. Even this house is in my hands,” she says from within the walls of a well built, brick home. “Every morning I wake up early to start a fire, sweep, bathe my children, make breakfast, iron my husband’s clothes, give him food, prepare my lessons. Even if you are educated, you’re entitled to every chore. It is a very big burden for women. They work all day long and sharing chores is impossible. If you try, they will say that you were not brought up well. This issue is everywhere. Girls are seen as inferior.”

What is your life like now?

“Now I am settled,” Mangochi replies, smiling and looking around her home, filled with nice furniture, a television, a stereo set with huge speakers, and decorations. “What I wanted most was to have a degree, and now I have one. I have to make sure my children finish their school. If I will have the means, maybe I can return to get a master’s degree.”

How are you unique from other Malawians?

“I’m very different. I’m unique. Not many girls or women engage themselves in studying science. But I did well in math and biology since Standard 1.” Mangochi continues to tell me how quickly she climbed the ranks during her career. At each school she has taught at, Mangochi has implemented extracurricular activities, something that most teachers fail to do. She has also been working to improve Khola Secondary since she arrived by generating funds to buy desks, sports uniforms, and eventually, bed nets. For many of her students, Mangochi is their favorite. “I like children. I try to engage them, to chat with them, to share food. Sometimes they come at night to tell me when someone is sick [in the boarding school].” Mangochi tells me that when planting season came, 15 of her students came to help plant, allowing her to finish an entire field in one day.

What is one thing about Malawians that you would want to explain to Americans?

“Malawians are hardworking. They have a lot of problems but they have their own way of persevering. We can handle it. We rely on one another so much.”

Thank you to Mrs. Mangochi for allowing me to interview her!

This post is part of Blogging Abroad’s 2017 New Years Blog Challenge, week two: The Danger of a Single Story.

5 Ways My Village is More Connected to the Rest of the World Than You’d Think: Globalization in Kasinje

For the month of January, I will be participating in a blogging challenge where I will receive topics to write about for each week in January. Below is my first submission!

This post is part of Blogging Abroad’s 2017 New Years Blog Challenge, week one: Global Citizenship.

Many of my fellow Peace Corps Volunteers and I live in the boonies. We traverse uneven roads while perched on uncomfortable bike taxis, we endure long minibus journeys, and we walk up and over mountains to access our sites. To reach the closest Peace Corps Volunteer, I must travel over two hours. Yet, despite this isolation, each day I am reminded of my community’s connection to the “outside world.” Contrary to the assumptions I had before coming to Malawi, my village is not an isolated entity where news of what’s happening in the capital takes weeks to arrive. My notions about Malawi’s disconnect from the rest of society, along with many other fallacies, have been shattered. Every day I notice countless ways in which my village interacts with the global community, whether it be through cultural, economical, or political exchanges. Here are 5 ways in which I’ve observed globalization in my own village:

1). Azungu BO! My first example comes from the vast amount of borrowed language that I hear spoken in Malawi. While there are over ten local dialects, each area utilizes “Chichewa-lized” terms, or words borrowed from other languages that are then made to sound like Chichewa (the national language). For example, foroko means fork, felempani means frying pan, sikulu means school, buku mean book, and poto means -you guessed it- pot. Some of them are so similar to English that it cracks me up! My favorite cognate, however, is bo, a colloquial way of saying hey. Anytime I walk around my village, I am inundated with bo’s or bo-bo’s. I’ve asked many people what the word means, but most have responded with kaya, who knows! I finally learned that it was adopted from French, either from bonjour or bon, meaning hello or good, respectively. Over time, bo morphed into an informal greeting and spread across the entire country of Malawi. Therefore, every day when chatting with my neighbors about how sikulu was that day, or saying bo to my friends, I’m reminded of how interconnected the world is based solely on common languages.

Bo-bo!

2). Luxury lakeside lodges. Within a few months of getting to my first site, I decided to bike from my village to Lake Malawi. I followed a tiny dirt path for about 15km, passing mud-brick houses with thatch roofs, children playing with makeshift toys in tattered clothing, and farmers hoeing away in their fields. The usual. When the path ended, I arrived at the beach and walked down the shore, wondering what I would find in the small fishing village. To my surprise stood a gated, three-story lodge with a manicured lawn, a pool, and a fancy Indian restaurant! I was beyond disbelief. Later I learned that a bit farther down the shore, on a little island, there sits a lodge that costs $300 per night per person! There I was, biking from my village in which the average person lives off of about $7-10 each month* to a lodge where tourists were spending over 40 times that amount in a single night. As more and more tourists visit Malawi -“tagging” their locations on Instagram, posting reviews on travel websites, or uploading photos on Facebook- the more exposure isolated places like these obtain. While exchange of cultures between tourists and locals can be wonderful for both sides, tourism can completely alter the lives and culture of local people.

Mayoka Lodge, Malawi

3). All of the stereotypes. Being Caucasian in Malawi not only warrants a lot of attention, but also generates countless assumptions. Almost everyone believes that I have copious amounts of money. They are astounded when I tell them that there are poor people in America. Many wonder why I don’t dress my dog in human clothing**. Others believe that the US has no trees and is just a big cement-filled city. Lastly, everyone thinks that all of my fellow American citizens have light skin. These stereotypes about Americans are most definitely perpetuated by globalization. Picture my neighbor, Malizani, going to the market and watching a film played on a shopkeeper’s TV. Most of what he sees is cheap action movies starring heterosexual, white Americans who live in big houses in the city. These quick glances into the lives of foreigners were not possible in rural villages even 20 years ago. Yet, with the help of foreign aid, Malawi has been developing its technology and infrastructure, allowing Malizani to form stereotypes about Americans. The spread of technology has perpetuated the spread of foreign cultures, values, and lifestyles into any space with a functioning television -whether they are true depictions or just something Hollywood has dreamed up. While many Malawians seem to rely on these stereotypes for their understanding of Americans (initially created by globalization), I believe that as we delve further into becoming one integrated, united world, we will all have a better understanding of each other.

4). Maize rules everything around me. How so? During the planting season, chiefs promulgate a change in livestock laws to protect sprouting maize. During growing season, teachers may not show up to school because they are busy weeding. During harvest season, it’s difficult to plan community projects because no one is around. After harvest season, there is a spike in weddings and initiation ceremonies when families know that their friends have cash to give. I think I could go on and on explaining how life revolves around maize in Malawi. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, maize accounts for 50% of the average daily calorie intake of Malawians. Imagine half of your plate at every meal being filled with maize! Five hundred years ago, this was certainly not the case. Malawians traditionally cultivated millet and sorghum, both drought-resistant crops. However, as the continent of Africa was “discovered” and colonized, foreigners brought with them preconceived notions on what would be best for African farmers, along with new plants. Specifically, the Portuguese brought maize to Malawi around 1500 AD. This fatal introduction has since led Malawi to depend almost exclusively on an extremely vulnerable crop for their staple food. (You only need to look at this year’s food crisis to understand the enormous impact that erratic rains have on maize, and therefore life, in Malawi). If Europeans hadn’t sought to expand their empire and forcefully insert their flawed-for-Africa farming knowledge, where would Malawi be? If Malawi hadn’t entered the global arena, would my neighbors still be farming millet and sorghum and therefore surviving the climate-change induced droughts that have been occurring?

5). I’ll flash you. One of the easiest, most obvious signs of globalization in my village is the widespread use of cell phones. When my mom was visiting in June, she wanted to take a picture of a woman carrying a hefty load on her head. However, when she noticed that the woman had a cellphone strung around her neck, my mom innocently commented that she wished it wasn’t there. The cellphone somehow marred the scene. While very unexpected for visitors, this clash of technology and tradition is now a part of Malawi. Technology has apparently jump-frogged development, bringing cellphones to people that can barely afford to feed their families. How does this related to flashing? In Malawi, to “flash” someone means to call their cellphone for a few seconds and then hang up so that they are aware that you are trying to reach them. This is done so the person calling does not have to use their precious and costly minutes. While most of my fellow community members have phones, few have the capital to make even a one minute long phone call every other day. The spread of new technology to remote areas can be startling and awkward, but has also brought great development to Malawi such as mobile banking and an increased ease of communication.

Hopefully you now have a better understanding of how Malawi can be affected by the rest of the world. As international travel increases, as technology spreads, and as language is adapted, the world shrinks. This interplay between cultures, peoples, and economies requires us to be global citizens. We must examine our choices. For example, is the lodge that I’m staying at exploiting a local culture or is it working with local groups to develop sustainable businesses? Is donating my old clothing “to Africa” really helping the people of Malawi, or is it impeding their textile industry? Are the crops that we are urging farmers to plant actually helping? Is donating tons of maize to Malawi each year just sustaining Malawi’s dependency on maize? Being a global citizen means educating yourself so that you can answer these difficult questions. It means extricating yourself from false stereotypes and not relying on media portrayals for your understanding of the countless different African cultures that exist. It means being aware of local cultures and how you present yourself when traveling. While I haven’t yet processed all that I have learned through Peace Corps, I do know that this experience has greatly encouraged me to be a true global citizen.

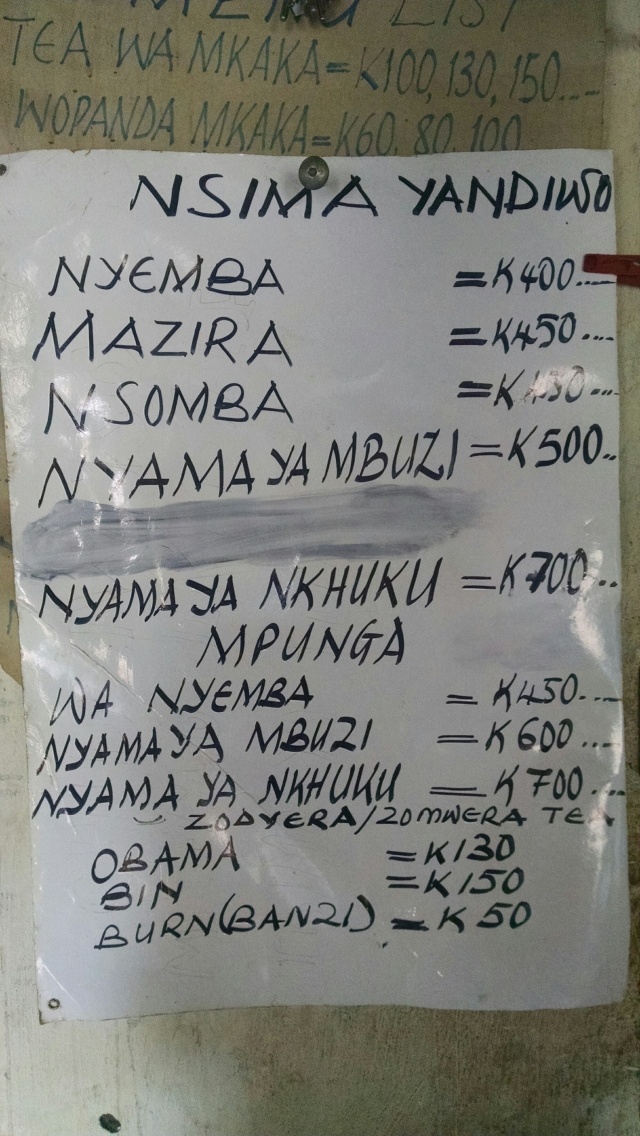

Bonus picture! This is a snap I took today in my favorite restaurant. Check out the third to last item on the menu, OBAMA. Yes, a popular bread here is named after The Obamas. I approve!

*According to a small survey I did in my catchment area

**Okay fine, I used to dress up my dog…

Top 5 Village Moments of 2016

As 2016 comes to an end, I’d like to share my top 5 village moments of the year. Although living in an isolated community far from friends and family can be incredibly taxing, it’s moments like these that make it all worth it.

1). One of my favorite moments I shared with my best little friend, Malizani. He is a boy in 3rd grade who comes over almost every day to read, draw, appreciate any new growth in my garden, or just chat. Malizani is incredibly polite and has a timid, quiet voice. (I’m guessing this is why I was drawn to him compared to all the other crazies). About a month after meeting him, he entered my fence (with permission of course), saw my face, and was overcome with astonishment. His eyes grew twice as big as he attempted in vain to prevent an embarrassingly enormous smile from spreading across his face. Apparently, every time he had seen me prior to this interaction, my hair had been affixed in a ponytail or bun. That day, I had shampooed and brushed my near-dreads and was letting my freshly conquered locks dry. Malizani slowly approached with a look of wonder and amazement. “Chiri…..” he cooed, wordless. He reached up and touched my hair shyly. “It’s beautiful…” he murmured, full of admiration. It was hands-down the cutest, most genuine compliment I’ve ever received.

2). Another favorite moment involves my landlord’s daughter/ good friend, Harriet. Harriet and her friend had come over to chat during the time I typically prepare dinner and asked what I would be cooking. I showed them my jackpot of carrots, green peppers, and green beans that I scored at the market. These types of vegetables can only be found on certain days and most community members aren’t accustomed to cooking them. Therefore, Harriet and her friend seemed quite apprehensive when I told them I was going to chop them up, mix them together, and fry them with an egg. I sliced off a bit of carrot for them to try, which they accepted cautiously, giggling with eachother and turning it over in their palms before finally tasting it. Their expressions immediately soured. Disgusted. Harriet spit it out. We all burst out laughing because I was clearly incredibly excited to be cooking my prized vegetables, while they were repulsed. The same pattern repeated with the green beans and peppers. They were incredibly hesitant to eat them raw, and even more grossed out to learn that I was going to cook them. In an attempt to persevere their image of me as a good cook, I brought out some soy sauce, which I figured they would appreciate due to their love of salt. “You see, the vegetables will taste good if I pour this over it!” I tried to explain. But again, they were repulsed. Another round of laughter ensued. Culture sharing can be wonderful, but other times you just have to agree to disagree I guess.

3). Another top memory of 2016 happened on my birthday in January, when I was still living in Maganga. I chose to celebrate with my best village friends, Ethero and Alakwanji, along with their younger siblings. Together, we made spaghetti and birthday cake, in addition to the traditional Malawian fare. We ate the spaghetti with our hands, lifting the slippery strands high above our mouths and letting them drop down. Having never experienced spaghetti before, everyone thought that the way the strands wiggled around in the air was hilarious and couldn’t stop laughing at how the spaghetti was “dancing.” It was all gone in a quick 20 minutes.

4). This next one is a bit longer than a “moment,” but I’m counting it anyway. Last year when I lived in Maganga, a student named Elijah volunteered to help me with a certain project. Flash-forward eight months and 110km apart later, (with no communication between us) and he randomly showed up on my doorstep one day! Apparently, his family is originally from a small village in the mountains 10km away from my new home in Kasinje. He had finished school in Maganga, returned home and heard that an azungu named Christina was living somewhat nearby so he came to investigate. He walked 10km from his home, asked around, and found me! What’s more, after catching up and eating lunch together, I told Elijah that I was lacking a counterpart that day. Mine had bailed and I was doing the same exact project that he had helped with in Maganga (Modern Malawians). He graciously offered to stay for a few hours and help. It was such a great surprise to see him and continue our work together!

4.5). This is a continuation of my story with Elijah. One day, about three months after his visit, I decided spontaneously that I would visit him at his home. I remembered the name of the village, Bonogwe, because it’s the word for a local vegetable. After asking my neighbors, they showed me the path to follow and I set off, quickly gaining elevation on a steep mountainous road. I passed only about ten men on bikes for the entirety of my journey. Most were dismounted, strenuously managing incredibly heavy loads that they were in the midst of transporting down to Kasinje. After a lot of sweating and heavy breathing, I arrived in a little village. A few huts dotted the landscape but as I continued, I found myself at the center of what I believed to be Bonogwe. It was a beautiful, forested little village nestled in the mountains, (the type that I wish I lived in!). I asked a man on the road if he had heard of a guy named “Elijah Ngwenya.” After a consultation with some kids nearby and repeating the name multiple times with different pronunciations, we finally understood eachother. “NGWENYA! Yes, follow me!” I trailed behind the man on his bike and we rode to a borehole. There, I was passed off to a bucket-bearing woman, who I was told was Elijah’s aunt. I had made it! We walked together to a Jehova’s Witness Church where I was passed off to yet another woman. Of course, the whole service was interrupted as I neared the door. I sat down as inconspicuously as I could, but everyone turned around and was staring at me. The pastor noted my presence and the children whispered. I had no idea why I was there. When the service ended, fifty people greeted me on their way out. I was then led to a house nearby by the woman who I later found out was Elijah’s other aunt. Over the next four hours, I met what seemed to be every member of Elijah’s extended family. The clan occupied a whole hill in Bonogwe, probably around thirty houses. I ate nsima with Elijah’s uncle, laughed with his young cousins, watched his grandfather make a hoe, and helped his aunt cook lunch. Yet, when the day was over, I never saw Elijah. It turned out he had moved to another village the month before. I loved this moment because it really does prove that you will be welcomed anywhere in Malawi, even if you don’t know a single soul in the entire village.

5). My last favorite moment comes again from an interaction with my friend Harriet. I was relaying a story to her (in broken Chichewa) and we couldn’t stop laughing. I told her that earlier that day, I had been lying in my hammock wearing *gasp* inappropriate clothing (shorts and a sports bra). All of a sudden, I heard the @&#_@#! goats that are always breaking into my fence and eating my crops. I practically fell out of the hammock trying to get up as fast as possible and started sprinting towards the fence where I could hear them knocking against it. “CHOKA! TIENI! TIENI!” I yelled in my scariest, deepest voice. “GO AWAY, LET’S GO, LET’S GO!” (There may have also been some inappropriate language in there). All of a sudden, as I neared the fence in a full sprint with my hands waving frantically, I realized that it was not goats at all, but Harriet’s father who had come to do some repairs to the thatch. Our faces were a mere foot apart with only the sparse, sagging fence between us. Instantly, I froze, shrunk down, and ran inside, pretending that nothing had happened. While I did not appreciate what had occurred in the moment, telling the story later to Harriet gave us quite the laugh.

Malizani, my best little friend featured in #1.

The Rain Gods

The arrival of the rains is truly a magical time in Malawi. Around early November, the rain gods begin to tease the country, gently tickling Malawi’s southern toes with light sprinkles. After nearly eight months with no rain, the softest touch of moisture is exhilarating. Though ephemeral, these early rains are a sign of change, a clue left by the rain gods that portend their certain return. Community members rush to prepare their fields, sculpting the land into long, elegant rows. Others begin fixing their thatch roofs, making sure to replace torn plastic and patch any holes. Meanwhile, the wispy rains tiptoe their way to the north and all dream of corn.

Then, one day in late November or perhaps early December, the “true” rains come. The rain gods open the sky, and out comes clean, fresh water that the earth eagerly accepts. The drops start gently, pitter-pattering on my metal roof. But soon they morph into heavy globs that crash down like cymbals above me and drown out the musings of Ira Glass. Outside, the leaves whip around their stems, clinging to the trees which they belong. The water comes in waves, blasting the roof and then retreating, blasting and retreating. Puddles begin to form. I stand on my back porch and survey what is usually a noisy, bustling scene outside of my fence. Yet everyone has retreated into their homes and all that remains is silence –a vacuum of noise that is not dissimilar from how it sounds to walk in the woods during a snowstorm. After ten or fifteen minutes, the rain gods tug a pulley, the sky closes, and the rain stops.

Gradually, the village speaks again. Bike taxis that sought shelter wheel out of their hiding spots. Ox carts continue their journeys. Kids call out to their friends and rush to the road, puddle-stomping in glee and trudging through newly formed rivers. The village is already livelier than it was before the rain, yet no new plant growth has occurred just yet. I walk out to the street and join my neighbors in awe of the transformation. It’s ten degrees cooler and the ground is a deep brown color. We hadn’t had a real rain 250 days. I smile and suppress the urge to run through the water like a madman, but choose instead to walk slowly and intently around my homestead.

The following day, everyone is in their fields and it feels like Christmas morning because planting season has finally arrived. This means food in three short months. I watch a farmer balance on one leg, push their opposite heel into the dirt and toss maize seeds into the hole. They then flick some dirt over the seeds with their toes and shuffle down the row. Over and over, they repeat this motion. Over and over, over and over.

In a few days time, the ground is covered with beautiful, green grass. In a few days more, the maize begins to sprout and the land becomes speckled with ankle-high nsima machines. It feels like springtime, my favorite season in the US. I plant my own vegetable garden, spread flower seeds, and create one single line of maize to appease/entertain my neighbors. Finally, hot season has come to an end. I thank the rain gods.

The Dreaded Minibus

Minibus drivers. They’re a different kind of breed. Aggressive, hot-headed and unapologetic, they have all the characteristics of an obnoxious, testosterone-exuding preteen trying to prove his worth. Yet somehow, they’re even more irritating. As you approach any bus depot (or in fact any place where there is a bus), they will swarm you like vultures to roadkill.

“Madame! Madame! Yes you are coming to Lilongwe! Come! Come!”

Oh… Am I? I thought I was just walking to the market to buy some flour…

These vultures flock to any body they detect. They yank your bags off your back and begin to pack them away before you can even process what’s happening. They slap down the metal chairs inside their buses, often hitting other passengers’ limbs and tell you to squeeze, squeeze, squeeze. They sloppily sling children off their mothers’ backs and toss them into the bus like a sack of potatoes. They rev their engines and tell you they are leaving “fast-fast” but then you spend an hour sitting still.

Minibuses are the only mode of accessible transport to the average Malawian. While there are scheduled “big buses,” these can be quite expensive and only travel between the major cities. Minibuses, on the other hand, will stop any point on the road– wherever there is an arm reaching out to flag them down. And often, they’ll stop when no one at all is flagging them down. “Hey look, there are two people facing the opposite way in deep conversation 100 meters from the road. Maybe they are looking for a ride!”

If you do in fact require a lift, the first step is to negotiate a price with the conductor. Without fail, he will name an astronomical price (especially if you are an azungu). Hopefully, you know the fare and can barter down to what’s fair. To miss this step is a rookie mistake. I’ve seen an agogo (elderly woman), who didn’t pre-negotiate, get dumped on the side of the road mid-route after refusing to pay the greatly inflated price of which she was just informed.

Your next duty is making sure your bags are safe. If you have a large pack, it will be shoved somewhere in the back amongst buckets of fish, sacks of maize, chitenje-wrapped luggage, a box of tomatoes, and a screaming goat. It’s important to keep an eye on the bag for you never know who might be violating your zippers and stealing your IntoCircuit 15000mAh Battery Bank that your parents just gave you for Christmas…

After settling in, your only task is to endure. Minibuses are overcrowded 99.9% of the time (according to my research) and you will never have enough room. Instead of sitting three to a row, conductors cram in at least four regular-sized humans with their respective children and bags sitting on their laps. (Picture the last row of that ol’ minivan you used ride in to soccer practice. Now, picture it stuffed with four large adults, two children and a rustling plastic bag with a live chicken head poking out of it). Due to the intense squishiness of the situation, your arms are trapped at your side, suctioned into the undulating shape of the voluptuous woman sitting next to you. Those trapped human arms have now been demoted to T-Rex arms. You can barely reach your forehead to wipe off the beads of sweat that have formed and instead, let them drip down your face. Did I mention that it’s hot season and 100 degrees out? The air you breathe is thick and filled with many interesting smells, including but not limited to: fish, baby poop, baby spit up, adult throw up, chickens, rotting tomatoes, goat, and of course, body odor. The stench is unbearable as no one, including yourself, is wearing deodorant. (In fact, you realize that you didn’t actually shower yesterday and feel a creeping guilt that maybe you’re the one who’s primarily responsible for the B.O.)

Further compounding your discomfort of is the fact that the distance between each row of seats is astonishingly minimal. Most of the time, your long American thighs cause your knees to be rammed into the back of the seat in front of you, offering another lucky passenger a bony, blundering massage. Unfortunately, there’s no way of adjusting your legs because directly under your feet is another sack of maize.

As aforementioned, minibuses are the only budget-friendly transport in Malawi. This means that even if a person is traveling from Nsanje to Chitipa (over 600 miles), they will be on a minibus. Aside from the lack of comfort, minibuses are notoriously and painfully slow. Some buses are delayed by heartless drivers who pull over in the middle of nowhere for a random 30 minute break. Others are slowed down by policemen, who saunter around the bus, “inspecting” it’s stickers while subtly looking for a bribe. And yet others delay themselves, purposefully driving slowly to maximize the number of passengers they can squeeze on. A five hour journey by car turns into a twelve hour journey by minibus.

Yet, despite all of these hardships, I have come to love and appreciate the sense of camaraderie and quirky smel—- just kidding. Minibuses are awful and I cannot wait for American transportation once again.